If you think THE EURO is anti-social, what do you think the US Dollar does?

| Last Updated: Tuesday, 6 February 2007, 14:09 GMT |

| Germans take pride in local money By Tristana Moore BBC News, Magdeburg, Germany | ||

| The next time you venture out for lunch in Magdeburg, check what kind of loose change you have in your wallet. Like any other city in Germany, the normal currency here is the euro. But bizarrely, they also have another currency in circulation: the Urstromtaler. Before you doubt its existence, it is not "Monopoly" money - it is very real. At a jewellery shop in the city centre, Gerfried Kliems explained how people use the regional currency. "It's quite simple," he said. "The money you spend stays in the region. When I accept Urstromtaler in my shop, I then have to see how I can spend the local banknotes. You get to know everyone who's participating in this project, and at the end of the day, you have a good feeling about life." More than 200 businesses are using the regional currency, including shops, bakeries, florists, restaurants. There is even a cinema which accepts Urstromtaler. 'Local boost' Frank Jansky, a lawyer, launched the regional currency in Magdeburg. "We are fostering links with businesses in the whole region and through the contacts that we develop, we are supporting the domestic German market," he said. "All the businesses have signed contracts, and it's official. We have our own banknotes and we have an issuing office in the city centre." At the Urstromtaler "central bank" in Magdeburg, which is no larger than a small office, the banknotes are issued at a rate of 1:1 against the euro. The banknotes have a time limit and lose value after a certain date, so people are encouraged to spend their money quickly.

Campaigners argue that the currency can help boost the local economy. "Everyone who uses the regional currency develops a social network. People get to know each other," said Joerg Dahlke. "It's also good for the environment, as you are not buying goods from big supermarket chains who import their goods. Instead you are buying products from regional producers," he said. It is easy to dismiss the regional currency as a gimmick, but supporters take it very seriously. "We are disillusioned with the euro, as it doesn't bring many benefits to the local community," said Joerg Dahlke. "But at the same time, we don't want to get rid of the euro completely. "Our regional currency runs in parallel to the euro. Of course, we still need the euro for big purchases," he explained. Residents can choose to pay one-third of their purchase in the local currency, and the rest in euros, or sometimes they can pay for their purchase entirely in Urstromtaler. The phenomenon is not limited to the state of Saxony-Anhalt. 'Social money' Regional currencies have sprung up all over Germany. According to Professor Gerhard Roesl, author of a report commissioned by the Bundesbank, there are at least 16 regional currencies in Germany.

"The regional currencies are not really a threat to the Bundesbank, although technically they are illegal and could pose a problem. The Bundesbank tolerates the local currencies, which are regarded as a kind of 'social money'," said Mr Roesl. Frank Jansky and representatives of other regional currency projects are lobbying the federal government to introduce a change in the law. "The Bundesbank is keeping an eye on what we are doing. Regional currencies are still in a legal grey area. But there are other comparable financial schemes, like 'miles and more', which also pose a challenge to the status quo," said Mr Jansky. "We are supporting our regional economy and culture, which will benefit future generations." And in case anyone thinks it's an old-fashioned system, they have now launched an online banking system for the regional currency in Magdeburg. | ||

http://www.rheingold-gold.de/index.php?seite=presse

In lands of the euro, a growing number of local currencies

ROSENHEIM, Germany: Christian Gelleri, with his straightforward manner of speech, rumpled suit and home office, hardly resembles the polished central bankers whose every breath captivates financial markets. But just as Jean- Claude Trichet, president of the European Central Bank, lays claim to the title "Mr. Euro," Gelleri can plausibly call himself "Mr. Chiemgauer."

Gelleri runs an organization that issues an alternative currency, known as the chiemgauer, that consumers in the region southeast of Munich use to buy everything from pizza to haircuts to rugs. Designed to foster the production and consumption of local products and services, the chiemgauer takes aim at the reigning central banking orthodoxy that pumping more cash into an economy accelerates inflation and eventually harms growth.

"When people use the chiemgauer, the apple juice producer sells more bottles and the cheese maker sells more cheese," Gelleri said. "In theory, this is not supposed to happen, but the fact is it does."

While more than 300 million people in Europe use the euro to buy life's essentials, a small but growing number — concentrated in the German-speaking world — use a proliferating species of currencies with names like chiemgauer, urstromtaler, landmark, kirschblüte and kann was.

Issued by private organizations, these currencies are probably better understood as vouchers — pieces of paper that can be redeemed for goods and services at specific regional businesses that have agreed to accept them.

By having charitable organizations sell them at a profit for euros, the organizations create an incentive for people to obtain them in the first place — on top of harnessing an altruistic desire to buy locally in an era of globalization — and businesses that accept can tap into a new vein of customers.

But they also typically include a feature aimed at jarring users into spending them more quickly than they would euros. In the case of the chiemgauer, the notes lose 2 percent of their value each quarter if people do not spend them in time.

Inspired by a long-dead German theoretician, Silvio Gesell, the currencies mine a hoary conflict in economics — usually pitting the mainstream against subversive outsiders — about whether paper money is a neutral medium of exchange whose purchasing power should be scrupulously guarded, or an instrument that could be manipulated to fulfill capitalism's untapped potential.

The contrast with the thinking behind the euro is stark. The ECB was given legal independence so that it would be free to pursue tough anti-inflation policies and stop politicians from embarking on ill-advised experiments in using monetary policy to spur Europe's economy.

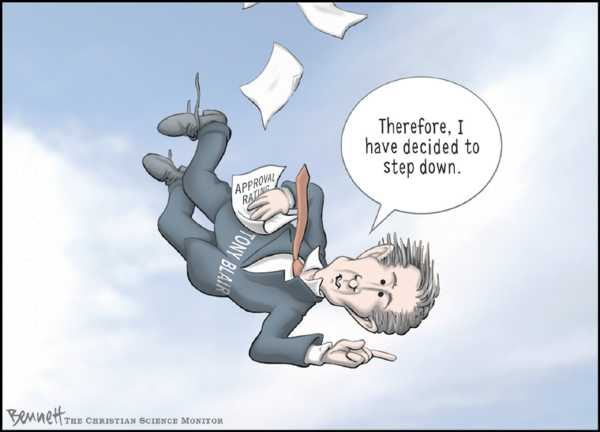

This independence periodically grates on European politicians, and seldom more so than now.

In December, Ségolène Royal, the Socialist candidate in the French presidential election this spring, opened an attack on the ECB and Trichet, saying that she wanted to make the bank "subject to political decisions." That prompted Chancellor Angela Merkel of Germany last week to voice "great concern" about criticism of the bank's independence.

Yet almost more than anywhere else, Merkel's own country has witnessed the rise of currencies like the chiemgauer since 2001 that embrace a theory that is probably more Royal than Merkel.

Regiogeld, a German association for alternative currencies, currently tracks 21 such types of money in circulation in Germany, Austria and Switzerland, with an additional 31 in preparation. Gerhard Rösl, an economist with the University of Applied Sciences in Regensburg, has also located similar experiments in Denmark, Italy, Scotland, Spain and Italy.

According to the Bundesbank, the German central bank, these alternative currencies are legal, provided they do not resemble the euro. But they are not legal tender like the euro and are unlikely to challenge the official currency shared by 13 European nations.

Rösl recently published a paper estimating the overall value of the currencies in Germany at €200,000, or $260,000, a drop compared to the trillions of euros in circulation. In a statement this week, the Bundesbank said that "only a very strong increase in these currencies would it disturb monetary policy."

Though their users emphasize that regional currencies complement the globally accepted euro, the money does embody a theoretical challenge to the common currency.

Gesell, a German émigré to Argentina and socialist activist, argued that money that sits in a bank was like dead weight on an economy, because it was accruing interest rather than being spent to fire consumption and production. Gesell proposed that money automatically depreciate over time — that is, inflation should be hard-wired into the currency — to generate an incentive to spend quickly.

The chiemgauer, named after the region around Rosenheim when it was created in 2003, follows this thinking.

To obtain chiemgauers, the roughly 1,000 users register with Gelleri's organization and get a bank card that resembles any other. At about 40 sites around the region, they can draw chiemgauers at the rate of one per euro, and spend them at roughly 1,000 businesses.

The chiemgauer depreciates at a rate of 2 percent per quarter, so Gelleri helped build in other incentives to persuade people to swap their euros for it. Schools, music clubs and elder-care associations, for example, sell chiemgauers and earn a 3 percent commission.

Users can also convert chiemgauers back into euros with the organization that issues them, for a 5 percent fee. If they overshoot the quarterly deadline for devaluation, they can purchase tiny stickers corresponding to the percentage lost which are affixed to the notes to restore them to their full value.

The currency's structure nurtures a psychology of spending to increase what economists call the "velocity of money." That way, even though the total amount of money in circulation may not rise — because euros get swapped for chiemgauers — the economic activity generated rises.

Alfred Licht owns a small family business in weaving rugs in Rosenheim, and estimates he has accepted 8,000 to 10,000 Chiemgauers over the past two years. He began accepting them as a way to lure customers who are interested in regional products. He spends them on medication, shoes and the occasional beer in a local tavern.

"I could hardly tell you how many I take in because I pass then on as fast as I can," Licht said.

Gelleri, a 33-year-old former economics teacher, contends that the statistics bear out the anecdotes. While the euro money supply turns over about seven times a year, the supply of chiemgauers does so at three times that rate.

Orthodox economists do not dispute that the chiemgauer's velocity outstrips the euro's, but they contend that people will logically draw fewer chiemgauers to protect themselves against the automatic devaluation. Rösl, the Regensburg economist, jeeringly calls the chiemgauer "schwundgeld" — "disappearing money" — to drive home his point.

"Yes, people spend the money more quickly," Rösl said. "But this money is expensive, because it loses value, so people are bound to hold less of it than they would otherwise."

Advocates like Gelleri say they believe they are doing more than simply putting Gesell's theory into practice. They are blending it with charitable work and support for the region.

The chiemgauer has earned money for the charitable organizations that sell the actual paper money for a fee — roughly €37,000 since 2003. And it has filled the coffers of Rosenheim's merchants and farmers.

Jürgen Wemhöner, a retired retail manager who estimates he spends several hundred chiemgauers a month, said the currency's appeal was that it supported the locals who accepted it. That seems to matter very much to people in Rosenheim.

"This currency gives small villages and regions a chance to survive," Wemhöner said.

But can a currency really do that for the Chiemgau region?

A central banker like Trichet might argue that prosperity comes from biting the bullet. Europe might suffer job losses and bankruptcies as it weathers globalization, but it will do well in the long term. The chiemgauer embodies an answer that is very different.

"With a little creativity we can avoid this suffering that we allegedly have to go through," Gelleri said. "The key is to do this intelligently, and we think it works."

http://www.iht.com/articles/2007/02/07/business/currency.php?page=1

Germans promote use of local currencies

BERLIN --A 10-euro bill buys a fine organic Riesling at the Alles Fliesst wine shop in Berlin's bustling Kreuzberg neighborhood. Or, as some regular customers do, you can hand the cashier something else: 10 locally printed Berliners.

Same goes for a jar of cinnamon honey, 4.20 euros or 4.20 Berliners, at the organic grocery upstairs, and for an espresso, 2.30 euros or 2.30 Berliners, across the street at the Cafe V vegetarian cafe, with its red ceiling, old chandelier and pipe-smoking clientele. The waitress even takes her tip in Berliners.

The Berliner, issued by a local environmental group, is one of around 20 local currencies that have begun circulating over the past five years in Germany. Concern about the impact of globalization and distant multinational corporations on their communities and locally owned businesses is one of the motivations behind making local money that will stay at home, community activists say.

About 10,000 Berliners have been issued -- printed by the Bundesdruckerei, the privatized former state printer, which also produces euros for Germany's central bank -- and they're accepted in 190 Berlin shops, many of them in Kreuzberg, a stronghold of Berlin's counterculture and the environmental Greens Party.

The Berliner is issued by the Gruene Liga, or Green League, environmental organization, at the wine shop, a cafe, a church, and a local alternative school. One Berliner costs one euro, and the League keeps the euros in the bank so shops that get Berliners from customers can turn them in for euros.

But the shops get only 95 cents back for each Berliner, with 3 percent going to local causes such as children's farm, a playground, and a church program for teens overcoming drug problems. Two percent funds a slightly better exchange rate to spur people to buy larger amounts of Berliners such as 50 or 100.

Activists have compared the slice taken by the issuer to the fees credit card companies charge -- the price paid for winning the business. Berliners come only in ones, fives and tens, so uneven sums can mean change in euros.

The principle behind a neighborhood currency is that it will be spent to support locally owned businesses and strengthen the community, said Suzanne Thomas, who leads the volunteer-run Berliner project.

"My outlook would be that you should obtain as many of the things you need every day from the local region, because if I have small shops in the street where I live, this adds to the quality of life," she said. "I can walk out the door and get what I need and not drive to some super shopping center."

She said the currency isn't a protest against the euro notes and coins, which some people blame for higher prices on some goods and services after they were introduced in 2002: "We think you should have both in your pocket, euros and Berliners."The practice of locally issuing micro-currency has been catching on in Germany since 2001, when the Roland was issued in Bremen. It has been joined by the Carlo in Karlsruhe, the Cherry Blossom in Witzenhausen, and the Chiemgauer -- one of the largest with more than 400 participating businesses -- in Bavaria's Chiemgau region; others have popped up in Basel, Switzerland and in Schrems, Austria.

The practice itself isn't new. Alternative or counterculture communities such as the Christiania hippie enclave in Copenhagen and the Damanhur group in outside Turin, Italy, issued their own money years ago. The Web site http://www.complementarycurrencies.org lists many different examples of currencies meant to be used alongside national currencies the world over.

In Germany, local notes equal to $388,000 have been issued, according to Regiogeld e.V., an association of regional currency issuers -- infinitesimal compared to the amount of euros in circulation and so small that it can't affect the euro's value, the Bundesbank says.

Even multi-culti, green Kreuzberg isn't exactly awash in Berliners.

At the Cafe V, owner Inci Cemil, 25, said the cafe might take in 10 Berliners a day. "We don't get any added profit, but we wanted to take part in the project," he said.

He said the Berliner could help boost local business such as the organic grocery, a valued neighbor where the cafe gets pasta, flour and bread. "I think people in Kreuzberg tend to support each other," he said.

A key feature of the Berliner -- and several other regional currencies -- is that it expires after six months and can be exchanged for a new one -- but minus 2 percent. That pushes people to spend it quickly and give an added kick to the local economy.

That idea, dubbed "schwundgeld," or "depreciation money," is based on the writings of Silvio Gesell, a German social and economic theorist who died in 1930. A 2006 analysis for the Bundesbank argued that the schwundgeld idea is seriously flawed and that the local currencies are economically inefficient.

Nonetheless, the Bundesbank said in a statement that the local notes do not violate German law so long as they are not intended to replace legal currency and don't look like a banknote.

People use the community-issued currency to support a cause, Gerhard Roesl of the Regensburg University of Applied Sciences wrote in his 63-page Bundesbank analysis. "These currencies offer a chance for the holder to demonstratively support the local region and to make a statement against globalization," he wrote.

He noted that several have appeared in German areas with low unemployment: "There, it seems, people can afford the luxury of 'disappearing money' more than in structurally weak areas."

On the Web:

http://www.berliner-regional.de

http://www.complementarycurrency.org

http://www.allesfliesst.debig read:

Wall Street and the Rise of Hitler

in short... Money is a fraudulent INVENTION, see the EASY EXPLANATION by way of this video:Money as Debt

http://www.google.com/search?q=%22money+as+debt