"The richest 2% of the world's population owns more than half of the world's household wealth. Half the world, nearly 3 billion people, live on less than $2 a day. The three richest people in the world – Microsoft Chairman Bill Gates, investor Warren Buffett and Mexican telecom mogul Carlos Slim Helú – have more money than the poorest 48 nations combined." ? — MSN Money Report, 12/13/2006

"Income in America is now more concentrated in fewer hands than it has been in 80 years. Almost a quarter of total income generated in the United States is going to the top 1 percent . The top one-tenth of 1 percent of Americans now earn as much as the bottom 120 million. The marginal income tax rate on the very rich is the lowest it has been in more than 80 years. Under President Dwight Eisenhower … it was 91 percent. Now it's 36 percent. " ? — San Francisco Chronicle, 10/24/2010

All money is debt... by someone.

http://tangibleinfo.blogspot.com/2011/10/idiocy-all-money-is-debt-no-debt-no.html

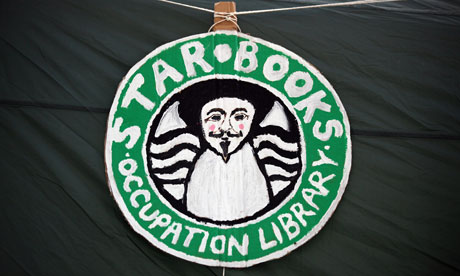

'Star Books' library at the Occupy London protest.

Graeber has linked the Occupy tented cities to the Arab spring, seeing both as signals of "the dissolution of the American empire".

Is Madagascar the model for Occupy Wall Street?

"Occupy Wall Street's most defining characteristics - its decentralized nature and its intensive process of participatory, consensus-based decision-making - are rooted in ... the scholarship of anarchism and, specifically, in an ethnography of central Madagascar," The Chronicle of Higher Education reports. "It was on this island nation off the coast of Africa that David Graeber, one of the movement's early organizers, who has been called one of its main intellectual sources, spent 20 months between 1989 and 1991. He studied the people of Betafo, a community of descendants of nobles and slaves, for his 2007 book, Lost People.

Betafo was 'a place where the state picked up stakes and left,' says Mr. Graeber, an ethnographer, anarchist and reader in anthropology at the University of London's Goldsmiths campus. ... 'Basically, people were managing their own affairs autonomously,' he says."

A key to unlock the door of debtor's prison

David Graeber's terrific new book, Debt. In the best anthropological tradition, he helps us reset our everyday ideas by exploring history and other civilizations, then boomeranging back to render our own world strange, and more open to change.

He tells, for instance, of the Tiv, residents of rural Nigeria with elaborate rituals of exchange spiked with a dark secret. Among the Tiv, it is known that the society of witches recruits by tricking someone into eating human flesh. After that, two things might happen. Ordinary people simply run screaming from the table. But those with the seed of a witch in their hearts are burdened with a flesh debt, doomed to give their family to be served on other witches' tables.

Only the most powerful and charismatic men are susceptible to the flesh debt. Although everyone wants to become powerful and attractive, it's a way of curbing a love of too much power. In the egalitarian world of the Tiv, the story prevents anyone from becoming too big for their boots, lest they be forced to cook their children.

Power and charisma used to be suspect in our own culture. Those who accumulated power, who manufactured and traded in credit, have generally not been loved. As Graeber notes, it's impossible to find happy stories about usurers in most cultures. Late capitalism is a strange exception. Bankers may be derided, but they continue to accumulate power and money, their social necessity defended by, say, Niall Ferguson, who suggests that poverty isn't about rapacious financiers exploiting the poor, but the absence of bankers for the poor.

Given bailouts for the wealthy and austerity for the poor, this is a tough case to make. What Graeber does is open the door to thinking more deeply about why bankers exist in the first place. Is the solution to poverty really about making microloans available (often at high rates of interest) so that "untapped" capital can be made to work? Or might we imagine our responsibilities to one another in different ways?

Graeber suggests that we can. For him, debt is "a relationship between two people who do not consider each other fundamentally different sorts of being, who are at least potential equals, and who are not currently in a state of equality – but for whom there is some way to set matters straight." It's a lovely definition because it reminds us of the possibility of equality. Of course, it also throws into stark relief the debt we're familiar with today, invariably based on the opposite of equality.

Getting back to equality means breaking with a conception of human relations as a series of purely selfish transactions. In spotting the roots of the idea that we're all basically selfish individuals in European thinking barely 500 years old, Graeber makes his case powerfully. Along the way, he helps explain why our modern talk is shot through with the language of debt, offering a theory of the rise of religion along the way. Why, after all, is Christ the Redeemer? What gets cashed in?

This is a big book of big ideas: Within its 500 pages, you'll find a theory of capitalism, religion, the state, world history and money, with evidence reaching back more than 5,000 years, from the Inuit to the Aztecs, the Mughals to the Mongols. Graeber might, though, have offered more about how debt happens within the home, and how people have sought to reconfigure relations of debt.

We're left with only one concrete idea about what to do next, but it's one that has precedent in many societies: a jubilee, a wiping-clean of the slate, in which we are reminded that the balance at the bank is not all we are, and that we might refashion our relations with one another differently, and better. If that ever comes about, we'll owe David Graeber one.

Raj Patel is an academic and activist whose most recent book is The Value of Nothing.

Another aspect: http://tangibleinfo.blogspot.com/2011/10/idiocy-all-money-is-debt-no-debt-no.html

comment

The book is packed with powerful insights and compelling perspectives. It's been one splash of cold water to the face after another, both awakening and invigorating.

"If you don't let us dream, we won't let you sleep".

They don't know why they're protesting

MSN MONEY writes:

The man behind Occupy Wall Street

Forget the labor unions. A University of London anarchist and anthropologist is a major force behind the protest movement.

If there is an endgame to the protests, he says it's to "delegitimize" the current political system in order to make way for the kind of radical change that would create a more open and fair democracy unshackled by the interests of big money."I think that our political structures are corrupt and we need to really think about what a democratic society would be like. People are learning how to do it now," Graeber says. "This is more than a protest, it's a camp to debate an alternative civilization."

In this interview, Graeber tells MSN-embedded-corporate-owned-mouthpiece MainStreet how he overhauled the message of Occupy Wall Street, why he wants to keep the list of demands as broad as possible and what he would say to those politicians who want to use the protests to their advantage.

MSN-MainStreet (office 14 Wall St, 15th Floor 212 3215000): How did you first get involved in Occupy Wall Street?

Graeber: I happened to be in the right place at the right time. There was a meeting on Aug. 2 for a general assembly to plan the Occupy Wall Street action based on an idea thrown out by Adbusters. Me and some friends showed up at this movement and sure enough there was a workers rally and we thought it was stupid. We said, 'Let's not play along, let's see if we can have a real general assembly.' So we started tapping people on the shoulder asking if they wanted to do a real general assembly and my friend jumped on stage saying we need to have a real general assembly and they chased her off. There was a tug-of-war, eventually we formed a circle, but it was back and forth and finally after a couple hours we managed to bring everyone away from their meeting into our meeting.

At that point, we decided on working by consensus process and we formed working groups and we decided to meet regularly afterwards. Then a couple days later we came up with the idea to call ourselves the 99% movement. I remember being the first to suggest this and was definitely the first to put it out on a list, though it was probably floating around at the time. That was really my key involvement.

MS: What was the movement like before you took control of it that day in terms of its goals and strategy?

Graeber: I think the coalition showed up on Aug. 2 and said they would do a rally and then show up on Wall Street with a list of demands that were total boiler plate -- a massive jobs program, an end to oppression, money for us not for whatever. They were nice people, but it wasn't very radical, just the usual demands.

Adbusters, when they originally threw the idea out there, they were basically marketing guys who changed sides. They thought like marketers and one of their schticks was to come up with one single demand. That makes perfect sense from a marketing perspective, but it doesn't make sense from an organizing perspective. You need to organize people around a list of grievances.

MS: Obviously, many people have criticized the movement for not putting out a single demand or list of demands. If the incentive to keep it vague was to make it easier for people to join the movement, why not make the message more specific now that the protests have gained steam?

Graeber: We don't want to give up the broad-based appeal. I do think every Occupy group has brainstorming groups coming up with this stuff, so there is a very long process of how we are going to come up with alternative visions democratically. That's being done. But people have been trying to put out demands and protest since the 2008 collapse and no one shows up. . . . Suddenly we get hundreds of thousands of people.

I think that people are much more interested in radical change. People really don't like the way things are arranged now. Yes, they have to actually get food for their children and that's a priority and if there is an immediate [political] measure that can do that then they want it, but there is an anger at the way things are structured. It's not a matter of how far people want to go as it is how far people think they can go.

MS: Given that, is there any issue you think the Occupy Wall Street protesters should avoid talking about, or is everything fair game?

Graeber: Antisemitic banking conspiracies and pretty much anything that's racist or sexist. Basic human decency applies. There are certain times that people say something that is offensive and people start repeating it in the human microphone. But we have working groups on anything else, where you can discuss monetary reform, where you can discuss transgender issues. It's a community with all sorts of concerns.

Thanks Occupy Wall Street . And we thought we were screwed, signed the 99 percenters who can't be there in person

MS: You seem to have a clearer sense of the purpose of these protests than most people, and you're certainly credited enough as being the architect behind them, so why not take charge of the movement more?

Graeber: I didn't want to do press stuff in the beginning, because I was involved with promoting my book ("Debt: The First 5,000 Years") and it seemed like a conflict of interest. We didn't have demands, and I had this book about debt, and I didn't want to make it seem like that's what we were pushing for. But I did do a lot of work with facilitation -- facilitating the first really long meeting at Tompkins Square Park, working with the outreach committee, getting together a training group for legal and medical training.

MS: And what about now? Clearly you are willing to do more media appearances, why not take your place as the face of the movement?

Graeber: I think the movement has many faces and that's as it should be. Sure, I'll be one of them, but when people ask, 'Was I one of the creators of OWS?' I say, 'Yeah, me and 100 other people.' It's the same with being a spokesman. I don't think I'm in any kind of privileged position. The last time I was in Zuccotti Park was 10 days ago, though I was in Austin [Texas] just a few days ago.

MS: Does it bother you, then, to see celebrities like Michael Moore and Cornel West appear front and center at many of the rallies, garnering much of the media attention?

Graeber: I don't think it's a problem that Michael Moore comes at all and I don't think that he has tried to become the face of the movement, but I do think if someone or some organization like MoveOn.org does try to become the face of it, that's a problem. I think these people are not trying to take advantage, they are trying to help, and I think it did help. NPR didn't cover this at all for the first two weeks and someone asked them why not and they said we would need to have tens of thousands of people, or we'd need to have more violence or we'd need to have celebrities.

MS: Was it really that hard to find a way to get exposure early on?

Graeber: We were in a trap because we knew that if you want media attention, you'd have to break some windows, but none of us wanted to endanger people or engage in violence. We all decided that would not be an appropriate tactic, but we knew the media would not cover us if we didn't. Then the NYPD obliged.

MS: You're referring to the scuffles between cops and protesters, I assume. Do you think the protesters did anything to incite those incidents or was it entirely the fault of the cops?

Graeber: The NYPD was absolutely given orders to intimidate people through random force. The very first day, four people were arrested for chanting in front of a bank. Another time, two people were arrested for writing with chalk on the sidewalk.

MS: Going forward, are you concerned that Democrats -- or politicians in general -- will make an effort to take over the movement and use it for their own advantage?

Graeber: I'm willing to believe that the Tea Party wasn't just Astroturf in the beginning, that it eventually got subsumed by Republicans. We won't let that happen. But I'll put it this way: If Nancy Pelosi is suddenly inspired to put out a call for a debt jubilee, that would be great. Nobody is going to say that's bad because it's backed by a government we consider to be illegitimate. That won't change our long-term visions. As long as you are on the same path, what we are really arguing for is what's possible so there's no reason we can't work together.

MS: And what exactly is that path you and the other protesters are working toward?

Graeber: That path is one towards autonomous organization. What this movement is about is that even the democratic institutions we do have now have been corrupted by big money, and in the same way our movement would be corrupted if we were subsumed into that same political system. We have to maintain the integrity of this experiment.

understand DEBT and MONEY:

http://tangibleinfo.blogspot.com/2011/10/david-graber-on-cnn-money-is.html

No comments:

Post a Comment