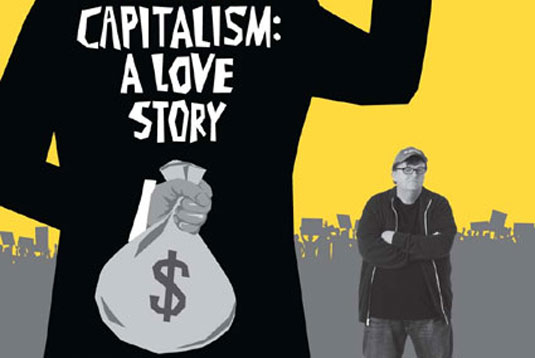

September 29, 2009

This is a follow-up to my review of Michael Moore’s “Capitalism: a Love Story” where I neglected to discuss his proposals for an alternative to capitalism, which boil down to worker-owned firms or cooperatives. He interviews the top guy at the Alvarado Street Bakery in California, whose website describes a cooperative as “an autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social, and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly-owned and democratically-controlled enterprise”. He also visits a robotics manufacturer in Wisconsin that operates on the same basis.

In an interview on Amy Goodman’s “Democracy Now” radio show, Juan Gonzalez asks a pointed question that gets to the heart of the matter: “Michael, you have obviously amassed a lot in terms of the indictment of capitalism as a system, but some would say the film doesn’t offer much in terms of the alternative.” Moore replies:

I do show in the film some very specific examples of workplace democracy, where a number of companies have decided to go down the road of having the company actually owned by the workers. And when I say “owned,” I’m not talking about some ding-dong stock options that make you feel like you’re an owner, when you’re nowhere near that. But I mean these companies really own it. And I’m not talking about, you know, the hippy-dippy food co-op, and I don’t mean that with any disrespect to the food co-ops who are listening or any hippies that are listening. But I go to an engineering firm in Madison, Wisconsin. These guys look like a bunch of Republicans. I mean, I didn’t ask them how they vote, but they didn’t necessarily look like they were from, you know, my side of the political fence. And here they all are equal owners of this company. The company does $15 million worth of business each year.

I go to this bakery. It’s not a bakery really; it’s a bread factory out in northern California, Alvarado Street Bakery. And they’re all paid. They all share the profits the same. They’re all shared equally, including the CEO. And they vote. They elect, you know, who’s going to be running this and how this is going to function. The average factory worker in this bread factory makes $65,000 to $70,000 a year, which, I point out, is about three times the starting pay of a pilot who works for American Eagle or Delta Connection. And that’s another harrowing scene in the movie, where I interview pilots who are on food stamps—pilots who are on food stamps because of how little they’re paid.

As someone who has paid fairly close attention to the airline industry over the years, I could not help but remember how worker ownership did little to stave off the race to the bottom in what was once a well-paying industry with excellent benefits. On July 7th, 1996 Louis Uchitelle informed his NY Times readers that worker ownership was no obstacle to the kind of downsizing that victimized the workers at Republic Window, whose sit-in was documented by Moore. Uchitelle reported:

Or take Kiwi Airlines, founded in 1992 by former Eastern Airlines pilots. It is 57 percent owned today by its 1,200 employees. But to cut costs, 60 owner-workers were laid off in January, many of them clerks whose jobs had been automated. “If we had done these layoffs earlier, there would have been revolution,” said Robert Kulat, a Kiwi spokesman. “We still had this concept of a happy family and of employees being bigger than the company. But big losses changed that. And people realized that to remain alive, to keep their own jobs, they had to change too.”

Interestingly enough, Uchitelle claimed that a strong union allowed United Airlines, another worker-owned firm, to avoid downsizing but only four years later economic reality caught up with the company, as the January 14, 2000 New York Times reported:

Faced with rising labor and fuel costs, the UAL Corporation, the parent company of United Airlines, said yesterday that its 2000 earnings were likely to be as much as 28 percent below expectations.

United Airlines, the world’s largest carrier, is being plagued by troubles that are common to the industry and by others that are singular to its operation. Jet fuel prices increased about 24 percent last year and United predicted further jumps this year.

Adding to the carnage, several of United’s unions were demanding large wage increases, in part to keep up with competitors and to replace money generated from the company’s expiring stock ownership plan.

“UAL gave a very sobering message yesterday,” said Kevin Murphy, an airlines analyst with Morgan Stanley Dean Witter. “No airline outperforms when you’re negotiating with labor. If United gives big wage boosts to its pilots and mechanics, the other carriers may have to catch up.

In 2001 United Airlines went bankrupt as a result of the impact of 9/11 on travel and rising fuel costs and was subsequently reorganized as a regular corporation. This had nothing to do with whether the company was “democratic” or not. Even if it was the most democratic institution in the world, it could not operate as a benign oasis in a toxic wasteland. Capitalism forces firms to be profitable. If they are not profitable, management takes action to make them more profitable, including slashing wages or laying workers off. The only way to eliminate these practices is to eliminate the profit motive, something that Moore is reluctant to advocate.

READ A MO(o)RE CRITICAL REVIEW:

It is understandable that Naomi Klein would have referred to the notion of worker owned firms this way in an interview with Moore that appears in the latest Nation Magazine: “The thing that I found most exciting in the film is that you make a very convincing pitch for democratically run workplaces as the alternative to this kind of loot-and-leave capitalism.” Klein, like Moore, has extolled the virtues of worker ownership in her own documentary “The Take”. This was my take on her movie:

In the opening moments of Avi Lewis and Naomi Klein’s documentary about occupied factories in Argentina titled “The Take,” we see Klein being hectored by a rightwing TV host. If she is not for the capitalist system, then what is she *for*. This is obviously is a tough question for autonomists like Klein who resist being pinned down, but she and her partner decided to make an attempt in “The Take.” Despite their best intentions, the film poses more questions than it answers. Ultimately, the film succeeds not as a political statement but as a record of ordinary workers trying to maintain their dignity.

For non-Marxist radicals like Klein, coming up with a model means first of all rejecting the USSR or Cuba which are dismissed as verticalist nightmares at the beginning of the film. The attraction of occupied factories in Argentina is that they are exercises in direct democracy, but do not involve the messy business of government, with its distasteful cops, courts and bureaucracy, etc. Of course, if you do not evaluate such institutions through the prism of class, you will never be able to operate politically on the most basic level. In the final analysis, cops will either support factories run by workers or they will evict them. Class power is the ultimate determinant of that outcome.

The film focuses on the efforts of workers to keep three factories running on a cooperative basis: Forja San Martin, Zanon and Brukman. Although Brukman, a garment shop, has only 58 workers, it is by far the best-known of these experiments. For autonomists, it has achieved the kind of mythic proportions that the St. Petersburg Soviet has for some Marxists. (It should be mentioned that the sectarian Marxist left rallied around Brukman as well, not so much because it was a model but because it was seen as an apocalyptic struggle between society’s two main classes.)

There’s a certain cognitive dissonance at work with Moore’s treatment of cooperatives. If it is a virtual panacea for what ails American workers, it amounts to a rightwing conspiracy when it is advocated as a solution to the health care crisis by Obama’s adversaries (of course, Obama is open to the idea himself.) If you go to Moore’s website, you will find an article by Robert Reich that makes a rather effective case against health insurance cooperatives: “Don’t accept Kent Conrad’s ersatz public option masquerading as a ‘healthcare cooperative.’ Cooperatives won’t have the authority, scale, or leverage to negotiate low prices and keep private insurers honest.” The same thing applies to outfits like the Alvarado Street Bakery in California or the robotics plant in Wisconsin. They lack the power to transform the American economy, just as health insurance coops would lack the power to safeguard the health of American workers. They would be nothing but tokens in a vast system operating on the basis of profit.

Despite its formulaic quality and despite some very dubious politics, I have no problem recommending Michael Moore’s “Capitalism: a Love Story”. Since there are so few movies (or television shows) that reveal the human side of the largest economic crisis since the 1930s, we must be grateful to Michael Moore for his steadfast dedication to the underdog. Except for Andrew and Leslie Cockburn’s American Casino, a documentary that covers pretty much the same terrain as Moore but without his impish humor, there’s nothing out of Hollywood that would give you the slightest inkling of the scale of human suffering.

There are two passages in “Capitalism: a Love Story” that I found particularly compelling. As an erstwhile analyst of airline deregulation, I thought that Moore’s interviews of a couple of low-paid regional airline pilots effectively illustrate how capitalism puts profits over human needs. One pilot was forced to go on food stamps while another had to take additional jobs to make ends meet. As Moore puts it, he would not want to step foot in a jet plane piloted by somebody making about the same money as a fast food employee. Other pilots, who are higher up on the salary scale working on nationwide routes, tell a similar tale of woe. After losing pensions and taking drastic pay cuts, they stick with their profession for the love of flying.

One of them is US Airways pilot “Sully” Sullenberger III, the hero who taxied his plane into the Hudson River, seen testifying before a packed audience in Congress about his rescue mission. But once he starts talking about the corporate attacks on airline workers, the politicians begin to sneak out like rats. He eventually ends up talking to a bunch of empty seats. This image–worth a thousand words–is Moore at his best. Another powerful image is the wreckage of a regional carrier Colgan Airline jet in Buffalo, New York from last February that cost 50 lives. Shortly after the plane crash, the NY Times reported that co-pilot Rebecca Shaw drew an annual salary of $16,200 a year and once held a second job in coffee shop. Both Shaw and the pilot were undertrained and exhausted much of the time. But it hardly mattered to Colgan if it remained profitable. If this isn’t an argument for socialism, I don’t know what is.

Since so much of the current crisis involves the housing market and its injustices, Moore hits a home run by demonstrating how politicians are bought off by the big players in the industry, especially Countrywide, the nation’s largest mortgage broker. He interviews an assistant to CEO Angelo Mozilo, who administered the “Friends of Angelo” program. This was a way of allowing elected officials to get discounted mortgages, including Senator Christopher Dodd, a Democrat with populist pretensions. As was the case with “Sicko”, there has been a major PR effort on behalf of the capitalist class trying to undermine Moore’s reporting. If you Google “Mozilo” and “Michael Moore”, you will find thousands of articles emanating from the same source that try to clear Dodd’s name as well as discredit Moore’s other claims. This one from Yahoo news is typical:

THE FACTS: Dodd has acknowledged that he participated in a VIP program at Countrywide, refinancing loans on two homes in 2003. One was a 30-year adjustable rate loan for $506,000 with an interest rate of 4.25 percent and a fee of 0.45 percent. He also got a 30-year adjustable rate mortgage for $275,042 with an interest rate of 4.5 percent and a fee of 0.73 percent.

Both interest rates and fees were within industry norms for that time, according to data provided to the AP by Bankrate.com.

Last month, the Senate’s Select Committee on Ethics cleared Dodd and Kent Conrad of North Dakota of getting special treatment on the mortgages. But the bipartisan panel also said the senators should have “exercised more vigilance” in their dealings with Countrywide to avoid the appearance of sweetheart deals.

One has to chuckle about the idea of a Senate Select Committee on Ethics clearing Dodd and Kent Conrad, another pig at Mozilo’s trough. It reminds me of how when the New York Police Department “investigates” an incident of police brutality, the malefactor is always cleared as well. The best tribunal for Dodd and company is the nation’s movie theaters where there are no special interests, except a desire to see bad guys nailed by the famous radical movie director.

I also got a big kick out Moore’s attempts to bust into the offices of AIG, Goldman Sachs and other financial corporations that received tax-payer bail-outs. As a former employee of Goldman who walked through the gilded doors at 85 Broad Street for about 2 years in the 1980s, I had to laugh at the spectacle of the bearish, baseball-cap wearing Moore trying to weave through security guards and into the lobby of by now the country’s most despised corporation.

Like “Roger and Me”, “Capitalism: a Love Story” contains autobiographical material about growing up in Flint, Michigan as the son of an auto worker. Moore’s father, who is still alive, escorts the director to the site of the auto parts company that employed him. Now it is nothing but a two mile wide vacant lot. Nowadays, the main industry of Flint is sending out foreclosure notices to the victims of the latest economic upheaval. Moore observes that the United States is rapidly turning into one big Flint, Michigan.

For Moore, the 1950s were a kind of Paradise Lost for the American working class. His father enjoyed four weeks of vacation every year and had enough money to participate in the post-WWII consumerist bonanza. Except for Jim Crow and the occasional imperialist war such as Korea or Vietnam, this was an unblemished society. Like many young people coming of age in the 1960s, Moore was deeply affected by these blemishes, so much so that he seriously considered becoming a Catholic priest, following the example of a Phillip Berrigan.

Moore’s revelations about his early religious leanings clarified for me what kind of compass he has been using from the very beginning in his career as a documentary maker. He has a deeply moralistic sensibility that is most often reflected as a kind of yearning for a more innocent and more egalitarian America, symbolized by his father’s good fortunes as an auto worker and the New Deal.

Although some critics have compared Michael Moore to Charlie Chaplin, I associate his moralism with the movies of Frank Capra, especially “It’s a Wonderful Life”. With the banks in his gun-sight, Moore evokes the struggle in this movie between an idealistic banker James Stewart and the evil banker Lionel Barrymore. There is a strong sense that Moore’s problem with capitalism is not that it is based on a class system per se but that it has broken a social contract established during the New Deal. His enemies are of course the Republicans but also the Democrats who abandoned FDR’s vision, starting with Jimmy Carter who is seen delivering a speech in 1979 with these words:

In a nation that was proud of hard work, strong families, close-knit communities, and our faith in God, too many of us now tend to worship self-indulgence and consumption. Human identity is no longer defined by what one does, but by what one owns. But we’ve discovered that owning things and consuming things does not satisfy our longing for meaning. We’ve learned that piling up material goods cannot fill the emptiness of lives which have no confidence or purpose.

Moore understands that the business about “piling up material goods” was a green light for American corporations to cut wages. What better way to get workers to become more spiritual than to reduce their earning power, after all.

Unfortunately, the Capraesque vision is ill-equipped to explain exactly why Flint and other rust belt cities hemorrhaged jobs from the 1970s onwards. Or why the banking sector was deregulated in a kind of New Deal reversal, leading to the marketing of derivatives and securitized mortgages. Were such decisions ultimately a failure of leadership at the top, when businessmen stopped behaving like good Christians?

There are glimmers of understanding in “Capitalism: a Love Story”. In one key segment, Moore shows exactly why General Motors earned the kind of profits that allowed his family to live well. He shows footage of the devastation in Japan and Germany following WWII. No wonder so many people bought Chevrolets. The competition had been bombed into rubble.

A real examination of the capitalist system would be far more systemic than Moore is capable of delivering. It would lead to the devastating conclusion that the groundwork for prosperity in such a system is war and nothing else. Periodically the system has a deep convulsion that leads to millions of deaths. If the current economic crisis is as intractable as the Great Depression, then the logical outcome would be a new global bloodletting with the unleashing of nuclear weapons. If this sounds suicidal, you must remember that an Adolph Hitler was ready to sacrifice every German life for his mad quest to build a thousand year empire. With the US in a far more prosperous state today than 1920s Germany, it is still capable of churning up the kind of madmen hounding Barack Obama. Imagine what this nation would look like if the unemployment rate ratcheted up to 20 percent.

There is one scene toward the end of “Capitalism: a Love Story” that really piqued my interest. For Moore, the formation of the UAW was a key historical step forward, an insight that naturally would come to somebody growing up in Flint. He reveals that his uncle was a sit-down striker in 1937, one of the biggest labor struggles of the 1930s. For Moore, a key element in winning union recognition was FDR’s deployment of the National Guard to Flint. Supposedly, FDR—unlike other presidents past and future—saw the National Guard as a pro-working class force. In February 1937, for the first time in history, the Guard protected strikers from the Flint police on FDR’s instructions and the battle for union recognition was won.

I have an interest in Flint labor history as well, mostly as a comrade of the late Sol Dollinger, a long-time UAW member and revolutionary socialist. Although not a participant in the sit-down strikes, Dollinger was married to Genora Dollinger who was a leader of the Woman’s Emergency Brigade in Flint in 1937. She was known as Genora Johnson at the time, married to Kermit Johnson at the time, a strike leader and socialist like her.

Sol Dollinger’s “Not Automatic”, a book about the Flint strike that depends heavily on Genora’s papers and recollections, paints a somewhat different picture from Moore’s. I reread Genora’s report on the sit-down strike, which is contained verbatim in Sol’s book. I also looked at the chapter on Flint in Art Preis’s “Labor’s Giant Step”, a book I read shortly after joining the Socialist Workers Party in 1967, Jeremy Brecher’s “Strike!”, and N.Y. Times articles from February 1937. Here is what all this material adds up to, from my admittedly far-left-of-center perspective.

To start with, the decision to send in the National Guard was made by Governor Frank Murphy, a Democrat who did have strong New Deal sympathies but those sympathies were not exactly in sync with the deepest aspirations of the strikers. Murphy’s intention was to get the strikers out of the factories and not to defeat General Motors. He hoped for a peaceful settlement of the strike and negotiations at the table. To put pressure on the sit-in, the Guard was instructed not to allow food to be sent into the factory. To my knowledge, the same pressure was not applied on the men and women who owned General Motors, who continued to enjoy three square meals a day.

Not long after the Guard was mobilized, Genora Johnson formed an Emergency Brigade of women who not only put their bodies on the line but dramatized the willingness of the entire community to come to the aid of the workers. Workers flowed into Flint from all around the industrial heartland in caravans, each one ready to confront any armed force that would be used against workers, either the local police or the National Guard. Additionally, many of the National Guardsmen were workers themselves who could not be relied on to shoot fellow workers. All in all, Murphy had to step gingerly around what was arguably the greatest display of working class militancy in the 1930s.

Flint auto strike, Genora Johnson at 2:33

The role of women in the formation of the UAW

To give some credit to Moore, he certainly does understand the need for such actions. A fairly lengthy portion of his film is shot in Chicago at Republic Windows, where workers were being screwed out of severance payments after the owners decided to shut it down. They sat in, determined to force the bosses to pay what was owed to them. However, in keeping with his tribute to FDR, Moore makes sure to credit the candidate Barack Obama who said that the workers deserved what the company owed them. At the time, many leftist supporters of Obama interpreted this as the second coming of FDR. In a way they are correct insofar as FDR came into office with the same loyalty to the big bourgeoisie as Obama. It was only the militancy of a desperate working class that forced him into taking a modicum of progressive actions.

However, these actions in and of themselves were not sufficient to break the back of unemployment. It took the hellfire of WWII and the cranking up of the arms industry to finally have the stimulus effect that led to postwar prosperity and all the rest that looms so idyllically in Moore’s memory. Humanity can not afford another cataclysm like this in order to sustain a consumerist economy that will eventually lead to ecological crisis of a scale never experienced before. In critical times such as these, it takes a deeper and broader vision of society than that found in “It’s a Wonderful Life”. It will require a willingness to break with class society and go deeper into the roots of the crisis than any Hollywood producer might be willing to bankroll.

How Goldman Backed Moore's 'Capitalism' Movie

Michael Moore's new movie, "Capitalism: A Love Story" opened today.

The first thing that must be said is that it isn't really a love story. Capitalism, Mr. Moore tells us, is "evil," and if his word isn't enough, he quotes two Catholic priests who say that capitalism is sinful and immoral, as well as Bishop Gumbleton of Detroit, who says that capitalism runs counter to the teaching of Jesus.

But if you can get past that – admittedly, a big if – there are some pretty entertaining moments in this movie. Mr. Moore is as tough on the Democrats as he is on the Republicans and the corporate executives. Democrats Richard Holbrooke, Donna Shalala, Senator Kent Conrad, and Senator Christopher Dodd all get skewered in the film for participating in Countrywide's "Friends of Angelo" program that offered favorable treatment for mortgages. Robert Rubin and Lawrence Summers are targeted for their big corporate paydays following (and, in Mr. Summers's case, also preceding) government service. Mr. Moore asks how Timothy Geithner got his job as President Obama's Treasury secretary, and the answer turns out to be, according to the movie, by completely screwing up as president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

The funniest moments of all in the movie, though, may just be in the opening and closing credits. We see that the movie is presented by "Paramount Vantage" in association with the Weinstein Company. Bob and Harvey Weinstein are listed as executive producers. If Mr. Moore appreciates any of the irony here he sure doesn't share it with viewers, but for those members of the audience who are in on the secret it's all kind of amusing. Paramount Vantage, after all, is controlled by Viacom, on whose board sit none other than Sumner Redstone and former Bear Stearns executive Ace Greenberg, who aren't exactly socialists. The Weinstein Company announced it was funded with a $490 million private placement in which Goldman Sachs advised. The press release announcing the deal quoted a Goldman spokesman saying, "We are very pleased to be a part of this exciting new venture and look forward to an ongoing relationship with The Weinstein Company."

Knowing that background puts the rest of the movie in a different context. Mr. Moore shows Rep. Dennis Kucinich asking rhetorically on the floor of the House of Representatives, "Is this the United States Congress or the board of directors of Goldman Sachs?" Later, Mr. Moore shows up at Goldman Sachs headquarters in Manhattan driving an armored Brinks trunk and announcing, "We're here to get the money back for the American people." Maybe Mr. Moore should look in his own pockets.

One could fault Goldman or Weinstein or Viacom for promoting or funding this sort of stuff – capitalist enemies of the predicates of capitalism – but in the end some of Mr. Moore's criticism is justified, and the rest is so farfetched as to be unlikely to do much lasting damage. Mr. Moore is right that Countrywide's "Friends of Angelo" program was outrageous, as was the federal bailout of Wall Street (which both Senator McCain and Senator Obama backed) and the fear tactics the Bush administration used to get Congress to approve it.

He's even right that capitalism is imperfect. But Mr. Moore doesn't make a convincing case that any other system would be an improvement. He offers some tantalizing glimpses of worker-owned and managed cooperatives such as the Alvarado Street Bakery and Isthmus Engineering and Manufacturing, and he suggests that things would be better if there were a 90% top income tax rate, stronger labor unions (like in Germany), and a second bill of rights added to the Constitution guaranteeing a job at a living wage, health care, housing, and education. He also seemed buoyed by a recent poll that found 33% of young Americans favored socialism over capitalism.

Interspersed with the credits at the end of the movie are a series of quotes from the founding fathers, including the one from Jefferson (discussed here yesterday, strangely enough) about how "banking establishments are more dangerous than standing armies," and one from John Adams to the effect that "Property monopolized or in the possession of a few is a curse to mankind."

Mr. Moore at one point shows a man whose home is being foreclosed on saying, "There's got to be some kind of rebellion between the people that's got nothing and the people that's got it all." But the reverence in this movie for the founding fathers and for the Catholic Church are in some ways not particularly rebellious at all. Nor is Mr. Moore's yearning for a return to the idealized capitalism of his childhood as the son of a GM worker, when unionized employees could enjoy pensions and four-week-long summer vacations, and families with one wage-earner were securely middle-class. "If this was capitalism, I loved it," he said. One gets the sense that Mr. Moore still loves that part of America that allows him to make a living by running around publicly criticizing big companies and politicians, the America that funds the camera crews and movie theaters that allow him to display and distribute his ideas. He may not realize that it's capitalism, but there it is. So maybe it's a love story after all, if not in quite the way that Mr. Moore intended.

Who should we believe? The propaganda from the past, or Moore's version of the present?

READ A MO(o)RE CRITICAL REVIEW:

No comments:

Post a Comment